The Singularity

There exists a hidden flaw in the monetary system, deep into the Black Hole... that could spell disaster for the Dollar.

Money creation, and by extension QE, is one of the most misunderstood practices in the modern financial system. Although some may claim only banks can create money- the truth is far more complex and nuanced than most would believe. And it hides a terrifying secret that is crucial to the Dollar Endgame.

Somewhere beyond the Monetary Event Horizon, in the crushing depths of the debt black hole, lies a point where all economic law breaks down-

The Singularity.

In a recent debate between Lyn Alden and Jeff Snider, Patrick McCormack opened with the crucial question- “Gun to your head, is QE money printing?” Lyn responded with a resounding “Yes!”, and Snider, in his typical fashion, read a statement from the Bank of Canada and concluded that QE was “no more than an asset swap”.

They’re both right. And wrong.

Let me explain.

Academics and bankers have long disagreed on the subject of money creation, usage, and even measurement. As early as the 1970s, estimations of the eurodollar money supply for example became incredibly hard to calculate. The Federal Reserve stopped measuring it for this reason, and later in 2006 halted calculations of M3 money supply as well. It was becoming simply too difficult for the government, or private institutions, to understand what was money or how much there was.

How did we get here?

In a address to the American Enterprise Institute on December 5th, 1996, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan laid out the importance of money as a tool for economic growth:

For, at root, money--serving as a store of value and medium of exchange--is the lubricant that enables a society to organize itself to achieve economic progress. The ability to store the fruits of one's labor for future consumption is necessary for the accumulation of capital, the spread of technological advances and, as a consequence, rising standards of living.

Clearly in this context, the general price level, that is, the average exchange rate for money against all goods and services, and how it changes over time, plays a profoundly important role in any society, because it influences the nature and scope of our economic and social relationships over time.

It is, thus, no wonder that we at the Federal Reserve, the nation's central bank, and ultimate guardian of the purchasing power of our money, are subject to unending scrutiny. Indeed, it would be folly were it otherwise.

The Fed is thus crucial for money- and is therefore “independent”, as a dependent central bank will be subject to the whims of politicians and will monetize government spending. As an independent corporation, the Fed is shielded from this undue influence, and is thus immune from causing disaster, and can foresee any problems arising in the monetary system, right?

Surely they, the masters of monetary thought, understand exactly how everything works?

Most monetary economics textbooks will tell you that:

Deposits entered into the banking system are stored as a sort of “reserve”. On top of this reserve new loans are created, in a levered ratio, such that $10 of deposits will allow for the creation of $100 of loans. Thus, the more deposits entered, the greater the loan capacity for banks.

Bank reserves are the primary capital upon which banks rely, and is set in a fixed amount by the central bank. These reserves are multiplied into base money by a static variable - “the money multiplier”. Thus, when central banks do QE, this creates more money. Lending is done directly based off reserves.

Both of these are incorrect.

In today's economy, the majority of the circulating money supply exists in the form of deposits, primarily held in banks. However, there is a common misunderstanding regarding how these bank deposits come into existence. The primary method for their creation is when commercial banks issue loans. Each time a bank creates a loan, it simultaneously generates a corresponding deposit in the recipient's bank account.

When households increase savings in bank accounts, these deposits are essentially redirected from potential deposits that would have otherwise been allocated to companies for the purchase of goods and services. Saving, in isolation, does not lead to a direct increase of deposits or loans.

To summarize the Keynesian view of banking, the quantity of reserves must act as a restrictive factor on lending, and the central bank must have direct control over determining the quantity of reserves. Although the money multiplier theory is a useful introductory concept in economic textbooks to illustrate banking, it doesn't accurately portray the actual process of money creation. In contemporary practice, central banks generally shape monetary policy by influencing the cost of reserves—specifically, interest rates—rather than directly managing the quantity of reserves.

In reality, reserves do not serve as a multiplying factor for lending. Similar to the connection between deposits and loans, the correlation between reserves and loans generally functions oppositely to the portrayal in economics textbooks. Banks typically make lending decisions based on profitable opportunities, crucially influenced by the interest rate set by the central bank. The quantity of reserves instead increase balance sheet capacity, such that a bank has a bigger book and potential to make loans but without profitable lending opportunities this potential will go unused. Think of it as expanding an auditorium- the overall capacity will grow, but the seats will not necessarily get filled.

This being said, lower amounts of reserves typically mean lower asset values and thus unwinding or deleveraging of the system. The Fed has been unsuccessful in lowering reserves consistently without a financial crisis or bank blowup occurring.

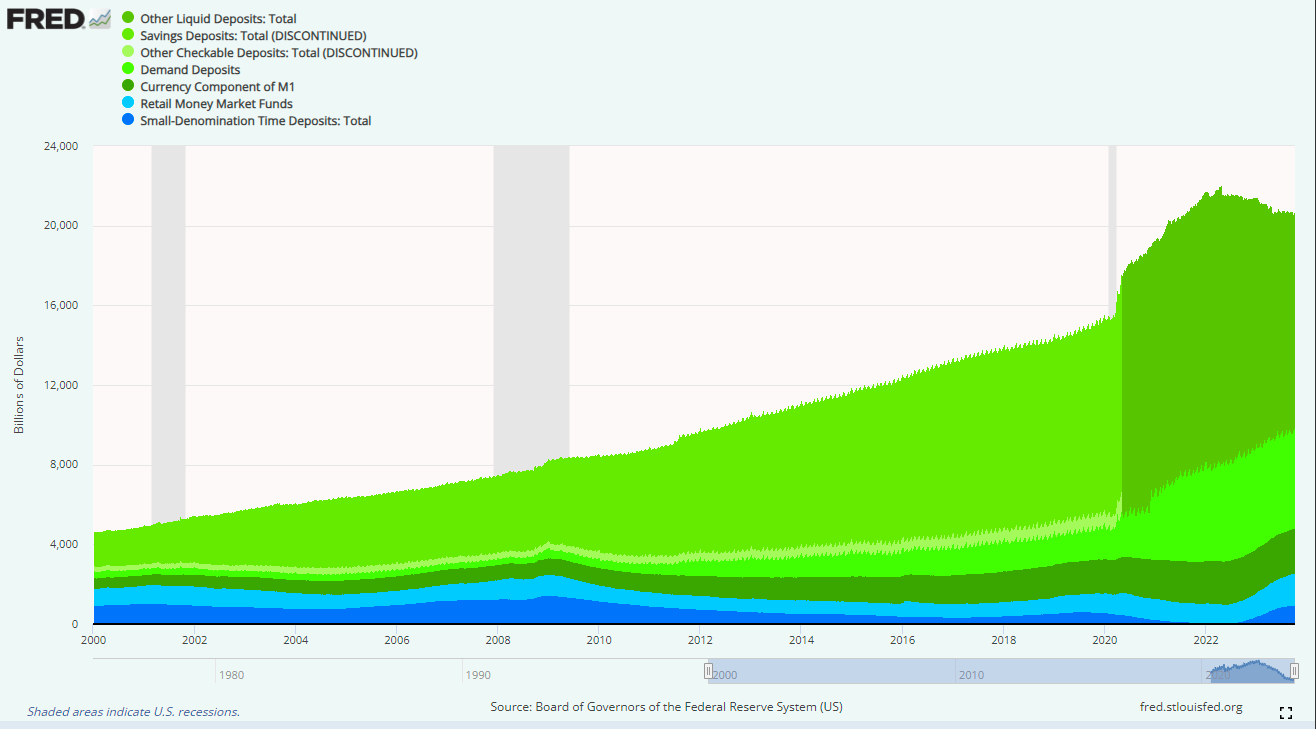

Broad money (M2) consists of two main components: bank deposits, which are essentially promises from commercial banks to households and businesses, and currency, primarily representing obligations from the central bank. Bank deposits constitute the overwhelming majority, accounting for 97% of the total amount currently in circulation.

This is important because broad money is what is available to spend in the real economy. It represents circulating cash, the amount of which directly impacts prices and therefore inflation. Tracking M2 is critical to understanding how the base layer (and real economy) works. M2 is the U.S. Federal Reserve's estimate of the total money supply- including all of the cash people have on hand plus all of the money deposited in checking accounts, savings accounts, and other short-term saving vehicles such as certificates of deposit (CDs). Retirement account balances and time deposits above $100,000 are omitted from M2, per the Fed.

Here’s a graph depicting the components of M2 so you can visualize it more easily.

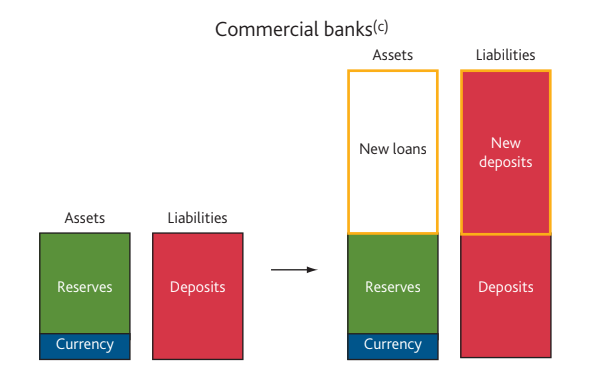

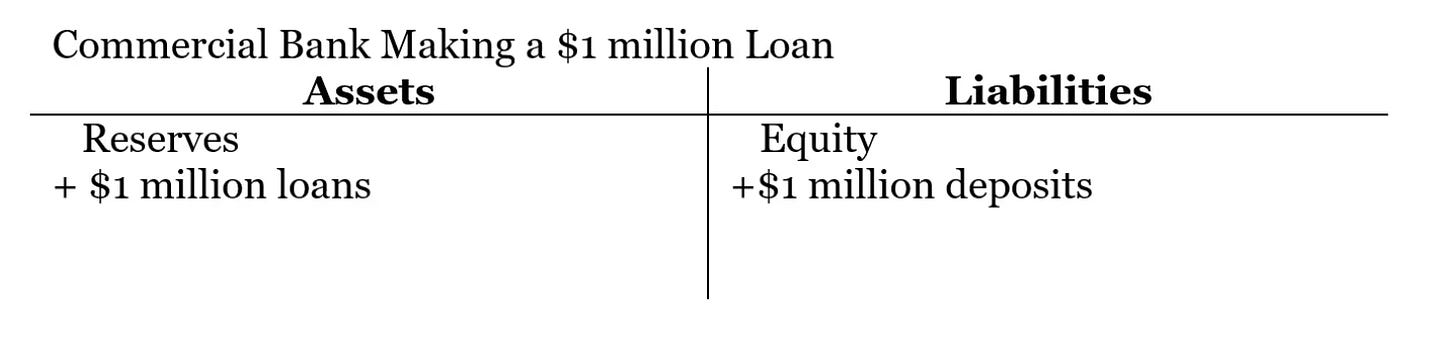

Commercial banks generate money in the form of bank deposits when they issue new loans. When a bank extends a loan, such as a mortgage for someone purchasing a home, it doesn't usually provide the borrower with physical banknotes worth thousands of pounds. Instead, the bank increases the borrower's bank account balance with a bank deposit equal to the mortgage amount. This instantaneously results in the creation of new money.

Here’s a diagram to visualize the process.

As this process continues, the size of the money supply and the debt load grow in tandem, working together to increase asset values and sustain a low latent level of inflation throughout the system. Because of the structure of this system, it is near impossible for consistent deflation to occur, as it means loans will default and money will be destroyed- causing a fall in asset values and thus collapse risk for banks which are fractionally reserved.

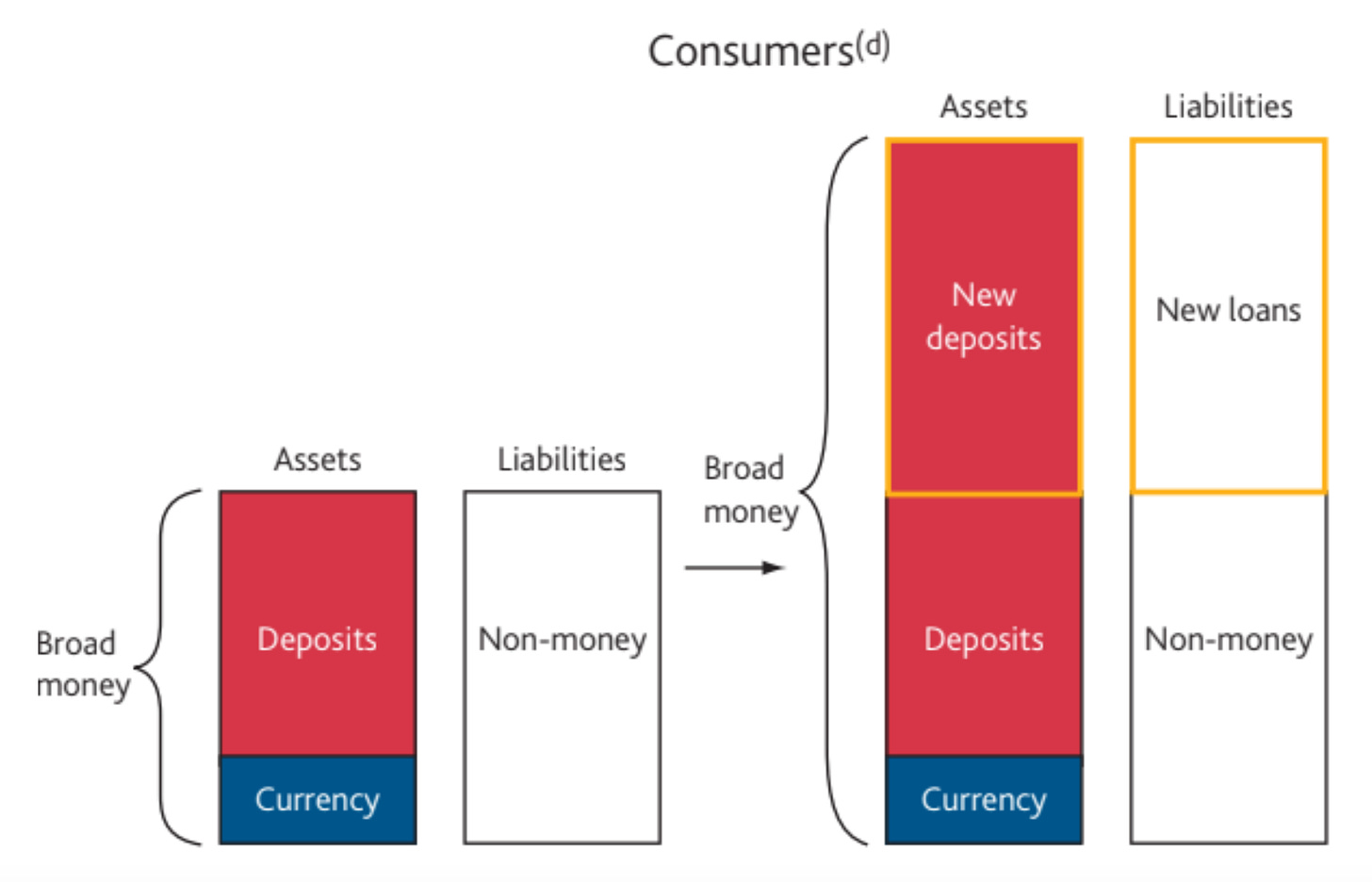

The freshly generated deposits boost the assets of consumers, symbolizing households and companies (illustrated as additional red bars), while the new loan augments their obligations (depicted as supplementary white bars). This results in the creation of new broad money. Likewise, both facets of the commercial banking sector's balance sheet expand when new money and loans are established.

Although new broad money emerges on the consumer's balance sheet, this occurs without an immediate adjustment in the quantity of central bank reserves or 'base money.' As we have already covered, the increased stock of deposits may lead to banks desiring or being mandated to retain more central bank money to fulfill public withdrawals or interbank payments- but it doesn’t mean those reserves are instantly created.

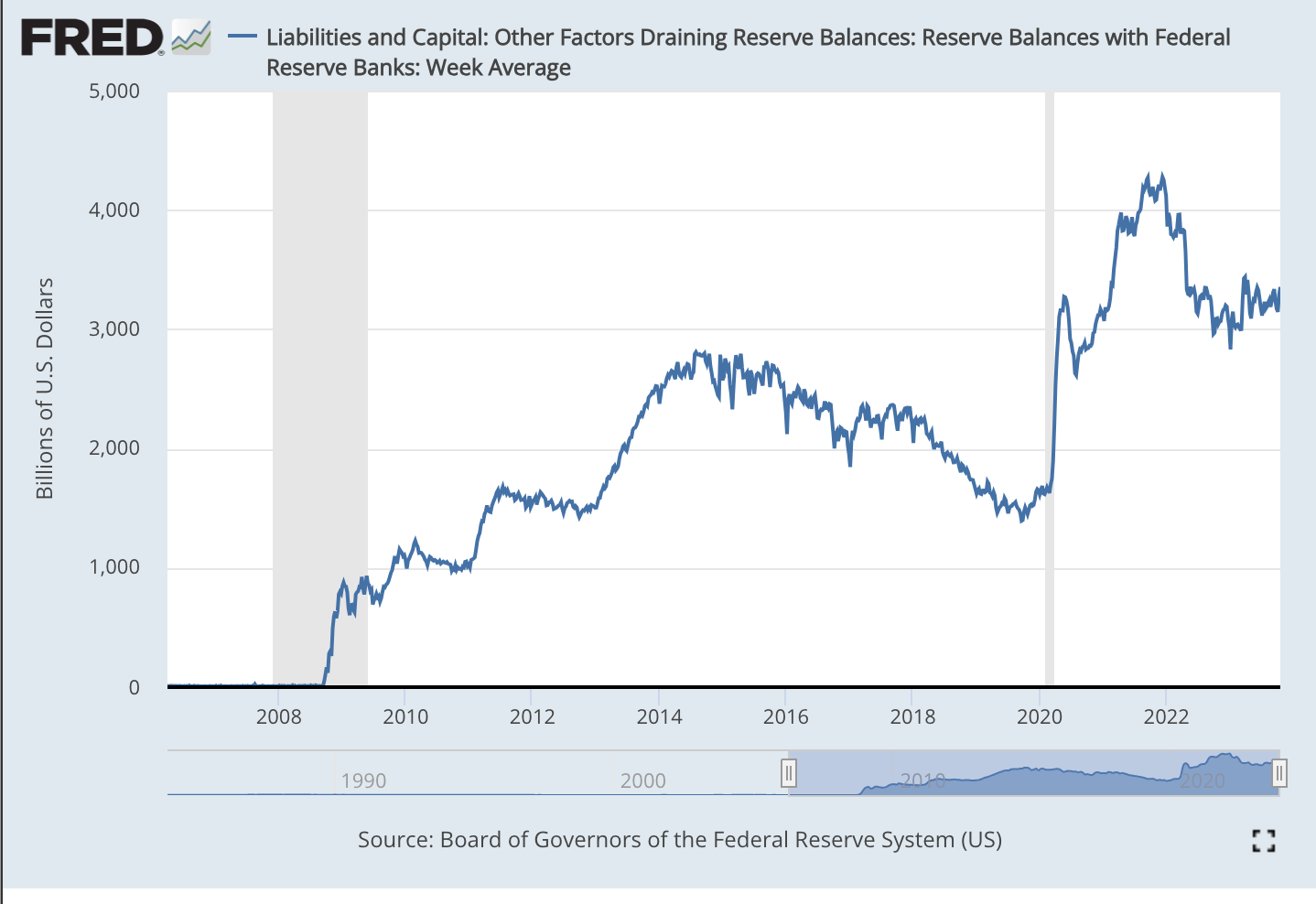

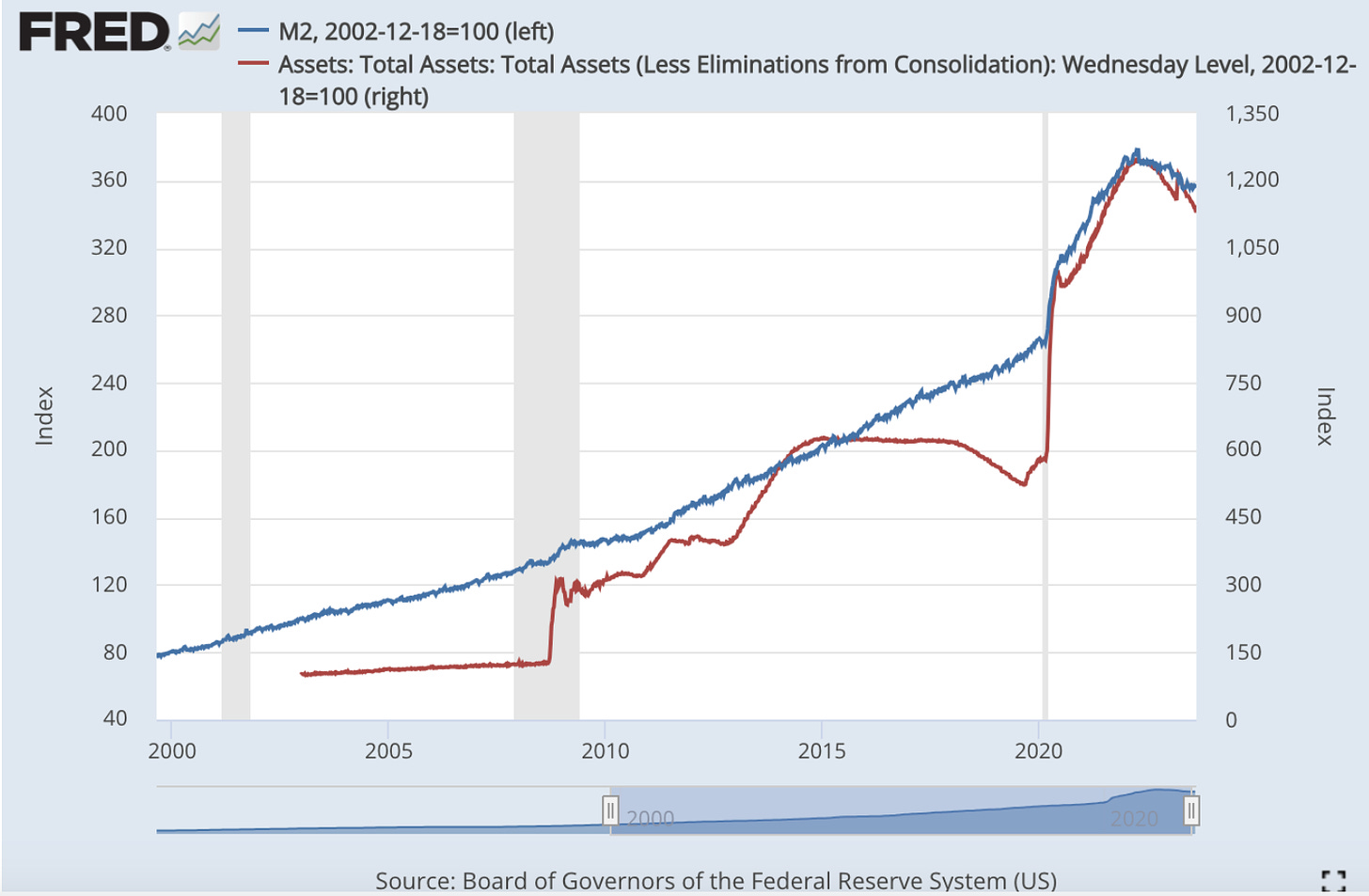

This is the driving reason why M2 Money Supply has been growing steadily for the last few decades, really for all of recorded history- even in periods without large monetary stimulus programs. Here’s a chart of M2 and the Fed’s assets indexed to 100 as of 2002- as you can see, M2 was growing slowly and steadily even before QE began and after the spike in QE in 2008, we did not see a corresponding increase in M2.

This is because bank reserves, which is what the Fed creates when it undergoes Quantitative Easing programs, are by definition NOT spendable in the real economy. They are trapped, rotating around balance sheets of financial institutions, used for collateral and funding arrangements to acquire securities or meet regulatory requirements.

Joseph Wang, a former senior trader at the Fed, explains it best in his article “A Two-Tiered Monetary System”:

Fed Reserves

Reserves are an unsecured liability of the Fed that can only be held by entities with an account at the Fed. Think of it as a checking account at the Fed, except that deposits in the account can only be used to pay entities who also have a checking account at the Fed. Broadly speaking, only depository institutions like commercial banks or credit unions are eligible to have accounts at the Fed. But there are also other notable entities such as the U.S. Treasury, GSEs like Fannie Mae, and clearing houses like the CME. When these entities make payments to each other, they pay in reserves.

[...]

Bank Deposits

Bank deposits are an unsecured liability of a commercial bank that can be held by anyone with an account at the commercial bank. Bank deposits are what constitute the vast majority of what people think of as “money.” When you logon to your online bank account, you are simply seeing how many bank deposits you have—how much your bank owes you.

Bank deposits are created when a commercial bank purchases assets or creates loans. When a bank makes a $1 million dollar to you, it is simply adding $1 million to your bank account. A commercial bank does not lend out bank deposits, it creates bank deposits. That being said, the commercial bank has to make sure its deposits are backed by sound loans and that it has enough liquidity to meet payments to other commercial banks.

Ok, so how do these two interact? And why is QE “sometimes” money printing and other times not?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Dollar Endgame to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.