I’ll be brief today, as I’m currently in Boulder, Colo., participating in a conference on “Renegade Futurism.” I’ll be speaking on a panel later about “AI as God,” which prompted me to revisit some things I’ve written about AI over the years. In lieu of a full post, I will republish a few parts of a newly relevant old essay on the subject, along with some brief framing remarks.

I can congratulate myself for being somewhat ahead of the curve in recognizing that the crucial arena for AI debates would be the realm of text (natural-language generating programs), which I explored in a conference presentation I gave back in 2015, five years before the watershed moment that was the advent of GPT3. (A brief version of my paper was then published in early 2016 here.) What struck me back then was that the emerging debate around algorithmic text generation echoed many of the themes of post-structuralist philosophy in which I’d been immersed for years. As I wrote:

[W]riting has long had the paradoxical status of being regarded both as a manifestation of inalienable human attributes, and as a technological prosthesis radically alien to, and separable from, the human person. This paradoxical status has occasioned a series of famous intellectual scandals, of which Plato’s critique of writing in the dialogue Phaedrus is the locus classicus. For Podolny, computerized writing forces us to reconsider the definition of the human; for Plato, it was writing itself that threatened to undermine the human subject of knowledge by outsourcing its most fundamental attribute—what he describes as “the living, breathing discourse of the man who knows”—to an uncanny simulacrum that “you’d think was speaking” yet remains “solemnly silent.” Fassler, writing in the Atlantic, finds the “eerily humanlike cadence” of Narrative Science’s products unsettling; Plato noted a similar eeriness in the way in which written texts mimic the flow of live human speech, yet stand at a disembodied remove from their origin. French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s project of “grammatology” traced the continuation of Plato’s polemic against the subversive power of writing throughout Western philosophy and literature. Western metaphysics, Derrida claims, has been constitutively phonocentric, locating truth and authenticity in the voice and regarding the written word as a degraded, mindless simulacrum of speech. While one hears echoes of Plato in recent articles that describe the “humanlike” qualities of algorithmically generated texts as “eerie” or “creepy,” what is lost is a sense that writing was already, for millennia, a distressing site of the technological uncanny.

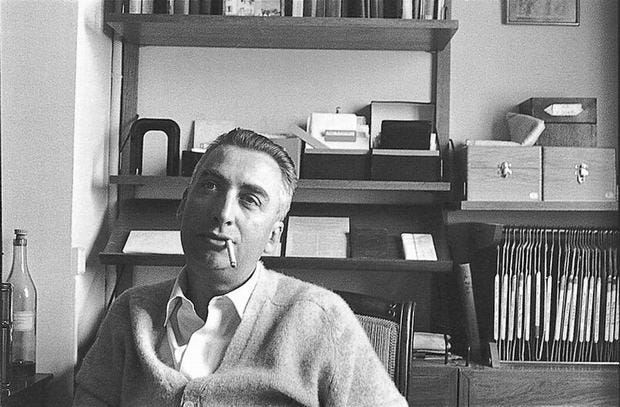

Precisely because of writing’s status as a decentering, destabilizing supplement to human subjectivity, the post-structuralist thinkers of the heroic age of literary theory took the declaration of the autonomy of writing as the starting point for a dismantling of the modern bourgeois myth of Man. Hence we find Roland Barthes, in his polemical essay “The Death of the Author,” affirming precisely what Plato feared: “writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where the subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing.” He goes on: “to write is, through a prerequisite impersonality . . . to reach that point where only language acts, ‘performs,’ and not ‘me’.” For Barthes and his successors, writing already forces the radical questioning of human essence that recent observers have linked to the impact of algorithmic text generation.

Yet what was also clear to me was that emerging AI startups’ de-throning of the humanistic Author-God—Barthes’s term—was more ambiguous in its effects than he and other prophets of this event had imagined:

For Barthes, as for Derrida and for the surrealists who pioneered automatic writing as an avant-garde practice, the death of the author was closely linked to the Nietzschean “death of God”: the liberation of writing from the conscious human subject was also, as Barthes proclaimed, a liberation from the understanding of the text as “a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the message of the Author-God).”

[But] NLG software’s creators and promoters account for its impact in terms that suggest the exact opposite. Here, for example, is Narrative Science’s description of Quill: “Every data-set, every database, every spreadsheet has a story to tell . . . Our advanced NLG platform, Quill, analyzes data from disparate sources, understands what is important to the end user and then automatically generates perfectly written narratives to convey meaning from the data for any audience, at unlimited scale.” It goes on: “There is a clear and immediate opportunity to bridge the gap between data and the people who need to understand it. That bridge is the power of a story. A story explains data, making it more understandable, meaningful and actionable.” Automated Insights’s slogan is in the same spirit: “Let your data tell its story.” “A line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning” would appear to be precisely the product on offer.

The lesson here, I concluded, is:

[T]he possible implications of available technologies of writing are one thing, while the dominant ideological construction of those technologies is another. For Plato, handwritten script threatened to undermine the self-contained autonomy of human consciousness, yet within the ideological framework of the Gutenberg Galaxy, as Kittler reveals, handwritten script was an essential attribute of human consciousness. The same technology that once seemed to threaten human essence ultimately came to ratify it; what Derrida called “logocentrism” can equally repudiate writing or fetishize it. It is therefore not inconsistent … that the developers of NLG software explain its significance in terms that suggest not the final eclipse of the “Author-God,” but the emergence of a new theology of writing and a new ideology of authorship, the creation of mechanisms to fix and constrain meaning, and the reinforcement of the reader’s passive status as receiver of that meaning. Such paradoxes, as this brief account has suggested, haunt the history of ideas about writing from the outset.

I’ve long intended to return to this subject at greater length now that NLG is everywhere, but haven’t managed it yet. So in the meantime, I’ll leave you with that, and as always, with the latest from Compact:

Frank Furedi on what accusations of political nostalgia elide

Phelim McAleer and Ann McElhinney on Harvey Weinstein’s new trial

Nathan Pinkoski on how Pope Francis brought managerialism to the Church

Justin Vassallo on why Democrats shouldn’t become the free trade party

Kirsten Thisted on how Trump has accelerated a reckoning with Greenland’s past

Adam Rowe on Trump’s intervention in the history wars

Sam Goldman on “Ralph Lauren Nationalism”

Thanks for reading!