If You Only Ever Play One Video Game, Make It BLUE PRINCE

MASSIVE post alert! also featuring: Sinners! Alchemy! Moomin!

Notes on a Video Game House

There will be no spoilers here.

There will come a moment less than two hours into Blue Prince where you think you have brushed up against its outermost limits - as a riddle, as a vessel for various puzzles, as an interactive work of art. You will feel annoyed, and stuck, and helpless. You will think you know what the game is up to. By the time you roll credits, a dozen hours after that moment, and a dozen hours before you’ll have come close to grasping the true shape of the text, you will remember that frustration as the moment the game truly began.

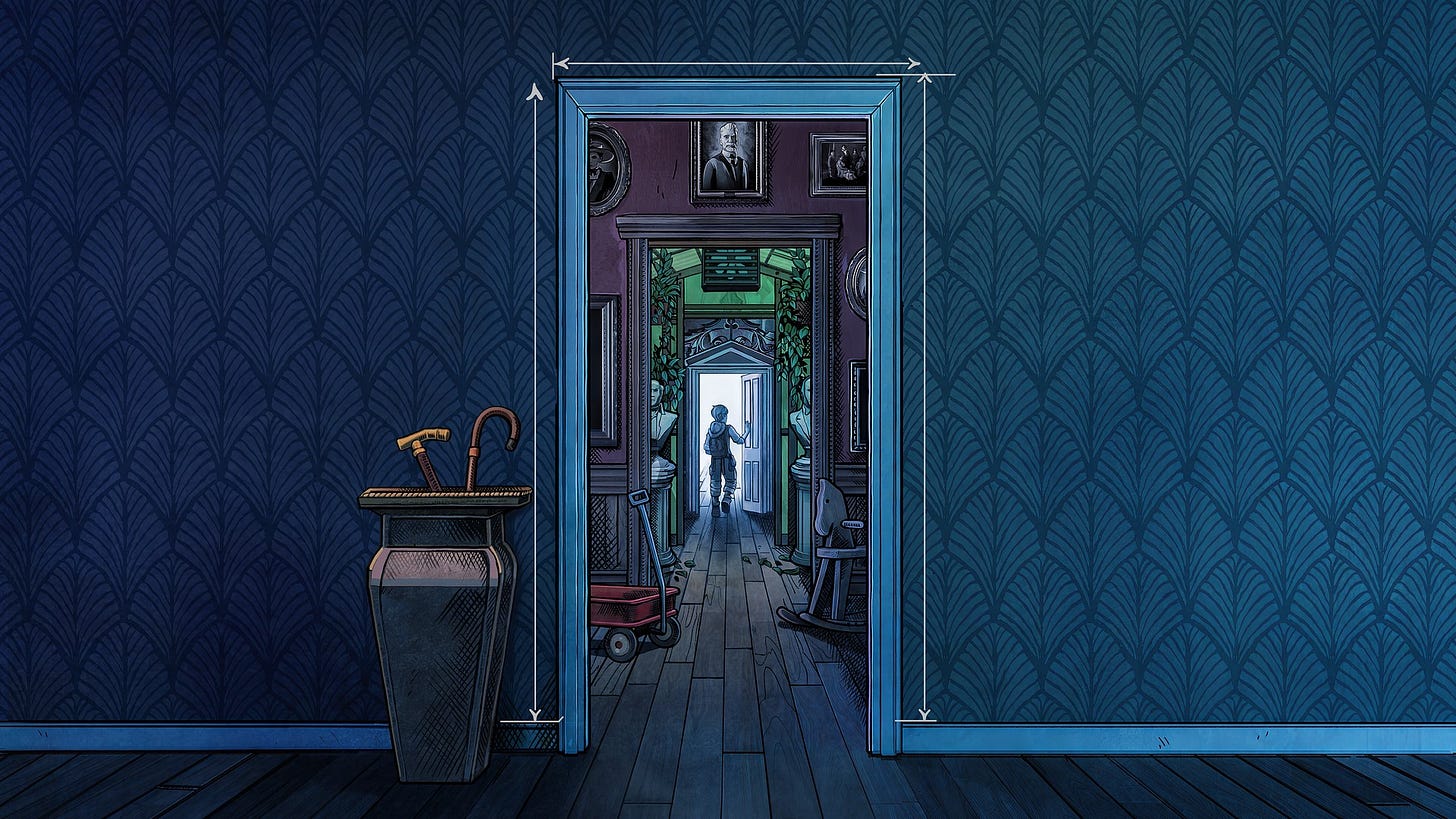

Blue Prince, the debut title from developer Dogubomb, is a game about a house. The house is Mt. Holly, your family’s estate. It is one house with one set of rooms that all look one way. There are 45 rooms in the house proper and you are in search of the 46th. If you can find it, the house is yours.

The gameplay is simple: The house is arranged on a 9x5 grid. When you enter a room, you “draft” it from a random selection of three offerings. These rooms offer different bonuses, disadvantages, items, and pathways. Some doors are locked. Every room has a name. Every named room has a single layout and no room appears more than once in a given house. Though certain items may spawn randomly, and certain interactions pull from a selection of riddles, the interior decoration, asset choices, and notes all remain identical. Your goal is to forge a path from one end of the grid to the other before your steps counter, which ticks down every time you enter a room, reaches zero. Whether there are no more rooms to draft or no more steps to take, the day will ‘end.’ Each day you begin with a blank grid. Each day the house has a new layout.

At some point you will reach the antechamber only to find all its doors sealed. At this point, you will begin searching for some clue as to how to unlock the door. You may find a room that invites a clear interaction with a specific item. You will optimize your play specifically to get that room with that item. You will try several times. You will end days with steps and room entrances to spare. One day you will get so close - item in hand, key room in sight - only to lack enough resources to draft it.

At this point, if you are familiar with game mechanics, it feels solved. It feels like the randomness has stunted the game in pursuit of novelty. You will want to claw at the wallpaper and sledgehammer through locked door. You will want to destroy the house.

Judged (unjustly) as a mere adventure game, Blue Prince lacks alongside its contemporaries. Outer Wilds relies entirely on the player’s growing knowledge to progress. Armed with adequate information, the world’s cycles are totally predictable. It is possible to beat the game on any day, given you have the knowledge and skill to pull it off. The same cannot be said for Blue Prince. On a given day, there are six puzzles you can work towards solving. Only one of them is obvious, and it’s probably the one you’ve already completed. There’s a good chance none of them will directly lead to finishing the game, and several are not meant to be solved until long after the game is properly ‘beaten.’ Approached as an old-school point-and-click, its evolutions feel like setbacks.

Conversely, last year’s Lorelai and the Laser Eyes - another title about an enigmatic house with interlocking mysteries of various complexity - has more and better puzzles. That is a more perfectly designed contraption, one that prompts the same compulsive obsession as the PS1 survival horror games that inspired the presentation. By the nature of its procedural-generation, you can go hours between ‘solving’ a puzzle and actually completing it. Struggling in Blue Prince does not feel like bashing your head against a riddle. It feels like wandering, blindly, hopelessly, through places you have already forgotten.

So you’re backtracking through the house, until maybe you stumble on a small note you missed. Or maybe you look up at the ceiling. Or maybe you draft one of the red rooms, which give you a debuff, just to see what’s inside.

And all of a sudden, the house, without changing, has exploded. The possibility space feels massive. The real-life notebook, which you previously kept as an obligation after some gentle encouragement from the developers, becomes essential. You scribble diagrams for brainteasers you have yet to encounter, lists of things left to do, secret drafting rules. Even when you’re not playing, you can’t stop thinking about it. You take pictures of on-screen lore text on your phone, only to pour over it on the bus later on. You will stop longing to demolish the walls of the house. Eventually you learn to trust Dogubomb’s years of rigorous playtesting. Every version of the house holds valuable intel, no matter how seemingly ‘unlucky.’ You are never without something to be gained from a given house, no matter what stage of the game you are in. Often, it just won’t be what you wish it was. The house builds itself inside you. You cannot halt its construction.

So yes, it is an immaculate executed game, one that stealthily invokes early dungeon crawlers under the guise of a modern roguelite walking sim. Blue Prince is a remarkable experiment in puzzle design. It’s so pretty, too, in its own Baby Gothic way. The cel-shading rivals Okami, and a delightful intermittent score worms its way into your head. Last week I woke up humming the main theme in the middle of the night.

But this alone does not explain how Blue Prince has moved me. The greatest accomplishment of Blue Prince is that they have built a house. It is a real house, in every way that counts. It is a house with history and logic to its decoration and construction. It is a house that cannot be mastered but can be learned, like the quirks of a childhood home. It is often actively antagonistic to your presence, even as it feeds you dozens of solutions. The game’s randomness is a reminder to pay attention, to embody the space as something beyond function or ambient aesthetic. It is a house that you will see differently from everybody else, but it is the same house, every day, for us all. It is a place that can only exist in digital space.

Blue Prince has a story. Its ending made me bawl unexpectedly, because it is not about characters or lore or The Meaning of Life. It is about interactive digital art and the places such a craft makes real. The game ends after that, likely whenever you choose to stop giving yourself over to it. Your playthrough is your own - even with every puzzle spoiled, the order in which you assembled its various pieces would be inherently unique, a personalized collaboration between player, designer, and software. Like the architecture of Mt. Holly, Blue Prince is steeped in the history of its form. The game file is quantum physics - it changes by simply being observed. There has never been anything like it.

Review code received for free courtesy of Raw Fury

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to cc: helmet girl to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.